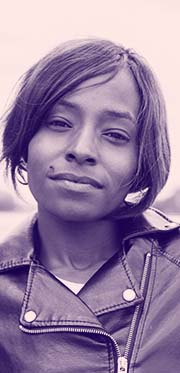

I met Beatrice four years ago when she was walking around trying to find people to help. I’m a current sex worker, I’m still an active drug user, and I was homeless for four years—like literally on the street homeless, not couch bouncing.

About a year and a half ago SWAN started having me give out harm reduction supplies so my backpack is like a part of me—I always have it on me. It’s filled with harm reduction supplies, like needles, cooker kits, wound care stuff, Narcan, and fentanyl test strips, which are so important. I try to get people to use them—I tell them it’s like a pregnancy test. If I get a bag of dope and I haven’t done it before I’ll test it. Now I help out on the van but I still carry the backpack every day. I feel naked without it.

I’ve spoken on panels for medical students about how people like me feel when we’re being treated in emergency rooms. I found that to be scary at first but it ended up being very cathartic for me.

When I’m telling my story, I really try to stress that I came from a wonderful family. My dad was a cop, my mom was a secretary … I became a drug addict. I’ll point at people in the audience, I’ll look them in the eye, and I’ll say, ‘I could be your mother, I could be your sister, I could be your daughter.’ People need to understand that just because it’s not happening to them that it can’t happen someday—like you might not have had cancer, but one day you might.

I’ve been told many times that I’m brutally honest so I have no problem saying what it’s like to be out there at 2:30 in the morning and being scared and beat up and robbed by somebody that you just had to service. And they just wanted to take the money back and brag to friends about it afterwards and leave you in the middle of nowhere. Or what it’s like to have a gun held to your head. It’s so important for people to know that nobody chooses to be in this position. That is what I really try to drive home.

I’ve been working with the SWAN van since they got it. I show up for work, I make sure I go to sleep at night, I don’t go home unless I have stuff for the morning so I’m not sick—I take it very seriously. I’m just a little person but I know I make a difference. Like last year I got hit by a car and broke my leg. I was in the hospital for 9 days. I came out—I’m on crutches, I’ve got my backpack, and this woman comes up to me and asks what happened. She got really emotional.

She was looking under the dumpsters for a dirty needle to shoot up with and after asking if I was OK she said, ‘Can I have supplies?’ Just by doing something that small, all of us little people are making a difference. It’s the big people that need to do a little better—I’m talking about way, way up there. There just really needs to be more money, more resources, more housing, more community action—and more tolerance.

This is not bragging but I am proud of it—I have nine Narcan saves myself, and most of them were people on the street that I know and love. I would like to say the majority of them are carrying Narcan all the time but they’re not. I know when I was homeless you’re constantly losing things so the Narcan is always getting lost. I’ve been in situations where I’ve been dealing with an overdose and did not have Narcan on me and I had to do mouth to mouth until the ambulance came. I tell people that all the time.

A lot of people don’t like to use the injectable naloxone but now we’ve got the nasal one they come in two-packs. I have a friend whose hustle is he rents his bedroom out to all the girls. A lot of guys pick up girls and they don’t want to do it in the car, they want a spot, so for $10 or $20 you can go to his house and rent his room. So because he’s always got girls there, I gave him a Narcan kit. I kept one Narcan, I gave him the other one, and a week later he saved my life with it. I overdosed in his house and he saved my life with that Narcan that SWAN gave me.